![]()

Railroad workers named Resaca, Georgia in the 1850's for the then famous Mexican War battle of Resaca de la Palma. By the 1860's it was little more than a village situated on the north bank of where the Western & Atlantic railroad crossed the Oostanaula River. Union Brigadier General William Grose described the area in 1864 as: "rough and hilly, interspersed with small farms, but mostly heavy woodland with thick underbrush." (OR No. 23) Please see "About our notes" for details on this web site's endnotes.

During the early years of the War Between the States, Resaca served as a staging area for troops from the deep south headed northward along the railroad to the battlefields in Tennessee and Virginia. Several local companies of Confederate troops were formed and trained there.

As the Union Armies moved into Georgia in early May 1864, the Confederate government granted General Joseph E. Johnston's persistent requests that reinforcements be sent to his Army of Tennessee, encamped in and around Dalton, Georgia. Those reinforcements consisted primarily of General Leonidas Polk's Army of Mississippi. Polk's forces consisted of two divisions of infantry stationed in Mississippi and a third division yet to be formed made up of odd units scattered throughout the Southland.

|

|

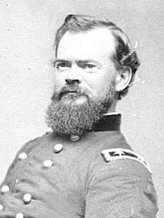

Brigadier

General James Cantey pictured here when he was Colonel of the First

Alabama Infantry.

|

One such unit was a brigade of infantry that had served garrison duty beginning in January 1863 at Mobile, Alabama commanded by Brigadier General James Cantey. By long marching between train rides, Cantey's men arrived at Resaca on May 7, 1864 and were originally ordered to continue on to Dalton. Southern cavalry patrols, however, alerted Johnston to the fact that a large number of Union troops were heading south from Dalton along roads that lead toward Rome, Georgia. Johnston characteristically decided to be cautious and telegraphed Cantey to entrench his men at Resaca. They had the rest of May 7 and all day on May 8 to prepare.

On the morning of May 9, 1864, Major General James B. McPherson's Army of the Tennessee emerged from the bottom of Snake Creek Gap with two veteran divisions of his XVI Corps and his entire XV Corps. His lead element, the 9th Illinois Mounted Infantry, quickly came into contact with a Confederate cavalry brigade under the command of Colonel Warren Grigsby that had been ordered to withdraw south from Dalton the day before and reconnoiter the area west of Resaca. Because of the nature of Snake Creek Gap, McPherson's troops were backed up and initially unable to bring the weight of their force to bear against their outnumbered foe. In heavy skirmishing, Brigadier General Thomas W. Sweeny managed to form a line and began to drive the Confederate cavalry back toward Resaca, a few miles to the east.

General William T. Sherman described his intentions for McPherson's force in his Memoirs. Upon being confronted with a strongly fortified Confederate position near Dalton, Georgia, he concluded that a maneuver aimed at his adversary's line of communications was in order. In his words, the position at Dalton "was very strong, and I knew that such a general as was my antagonist (Jos. Johnston), who had been there for six months, had fortified it to the maximum. Therefore I had no intention to attack the position seriously in front, but depended upon McPherson to capture and hold the railroad to its rear, which would force Johnston to detach largely against him, or rather, as I expected, to evacuate his position at Dalton altogether." (Sherman, p. 496)

It is obvious from this Sherman intended that, one way or another, a battle would be fought at Resaca. Unfortunately for him, however, things didn't exactly go as planned. McPherson personally directed Major General Grenville Dodge's XVI Corps forward. Major General John A. Logan's XV Corps followed close behind. Grigsby's cavalry skirmished with the Federals every step of the way until the Southerners were able to withdraw into the outer line of a series of fortifications constructed near Resaca. There the 37th Mississippi, a Regiment of Cantey's Brigade, reinforced the cavalry. This particular line was on what was described as "a bald hill" and had been hastily prepared. Against this Dodge sent in a brigade of infantry supported by artillery, and the 66th Illinois Regiment armed with Henry 15-shot repeating rifles (Castel, p.137). This attack easily drove the Confederates all the way across Camp Creek about mid-afternoon.

So far so good. In fact, when Sherman received a report as to the Union progress (which didn't reach him until supper time that evening) he made his often quoted exclamation: "I've got Joe Johnston dead!" (Scaife, p. 22). Now McPherson ordered Dodge to send the 9th Illinois Mounted Infantry (his only available cavalry) north and east to find the best route to the railroad. Meanwhile, Dodge's skirmishers cautiously approached a formidable line of fortifications east of Camp Creek. In it were not only Grigsby's cavalry and the rest of Cantey's Brigade, but also a brigade of infantry under Brigadier General Daniel H. Reynolds that had just arrived at Resaca. In addition, the Confederates had in place at two batteries of 12-pound Napoleon field pieces.

Dodge described these actions in his official report: (The 9th Illinois Mounted Infantry) "struck the railroad about two miles south of Tilton (which they found strongly patrolled by the enemy's cavalry) and succeeded in cutting the telegraph wires and in burning a wood station, reporting to me without loss at dark. About 4 p. m., I received orders to advance my left, the Fourth Division, to the railroad north of Resaca, and hold the Bald Hill with the Second Division. General Veatch was immediately ordered to move, with Fuller's and Sprague's brigades, of his (Fourth) division, massed in close column by divisions, and, forming promptly, he moved rapidly across the west fork of Mill Creek, in plain view of Resaca. The enemy, observing the movement, opened a heavy fire from his batteries upon the column, and also, together with rapid musketry, upon the left of the Second Division, doing, however, but little execution. After having moved the column across the first open field, I received from General McPherson an order directing me to look well to my right, as the enemy was massing and pressing forward in that direction. Colonel (now Brigadier-General) Fuller led the advance of the column, and, just as he was gaining cover of the woods on the east side of Mill Creek, I received notice that Colonel (now Brigadier-General) Sprague's brigade had been halted. My order of General McPherson, to support the left of the Second Division and hold the space between that division and the Fourth Division. I was with the advance (Fuller's brigade). The skirmishers had just reported that they were within a short distance of the railroad when the enemy opened fire upon the brigade with a regiment of infantry and a battery in position, directly on our right. I immediately sent orders to Colonel Fuller to charge the battery and swing still farther to the north, under cover of the timber. Before this order was executed I received orders from General McPherson to withdraw the brigade and close upon Colonel Sprague, who was formed on the left of the Second Division. This had to be done in view of the enemy, whose batteries had a point-blank range across the open fields upon the column. Colonel Fuller deployed his brigade under cover of the timber, and, withdrawing by regiments across the open fields, formed in position on the west side of Mill Creek. By the time the withdrawal was accomplished it was sunset; and I received orders to withdraw the command and retire to Snake Creek Gap." (OR No. 524) Note: Dodge's reference to "Mill Creek" here pertains to Camp Creek.

What happened to the assault? By mid-afternoon the town of Resaca was in plain sight, defended by a force that McPherson outnumbered at least 5 to 1 and, more importantly, his Federal army was less than a mile from the railroad that served as Johnston's vital line of communications. As his official report indicates, however, other issues plagued his perspective. He became acutely sensitive to his exposed position and retreated back to Snake Creek Gap. There he fortified his lines and awaited for Sherman to send more troops through the gap. He would not advance again until May 13.

|

|

Brigadier

General James B. McPherson

|

First of all, McPherson had no idea how many Confederates were entrenched before him at Resaca. The Southern delaying tactics throughout the day and their fierce demonstration in the face of the Northern army certainly revealed no inherent weakness. McPherson wrote in his official report of May 9 that: "The enemy have a strong position at Resaca naturally, and, as far as we could see, have it pretty well fortified. They displayed considerable force, and opened on us with artillery." (OR No. 437) Obviously, the Confederate performance made an impression on the Union general. But, there is more to it than that. McPherson's force was sent through Snake Creek Gap without any cavalry other than the 9th Illinois. He had no way to investigate any portion of the field beyond what his infantry could see. Also, there were logistical considerations to his decision. He explained:

"I decided to withdraw the command and take up a position for the night between Sugar Valley and the entrance to the gap for the following reasons: First. Between this point and Resaca there are a half dozen good roads leading north toward Dalton down which a column of the enemy could march, making our advanced position very exposed. Second. General Dodge's men are all out of provisions, and some regiments have had nothing to-day. His wagon train is between here and Villanow, and possibly some of them are coming through the gap now, but they could not have reached him near Resaca; besides, I did not wish to block up the road with a train. It is very narrow, and the country on either side is heavily wooded. I had no cavalry except Phillips' mounted men to feel out on the flanks." (OR No. 437)

When Sherman received the news of McPherson's decision later on the evening of May 9 he was bitterly disappointed. "He had twenty-three thousand of the best men in the army," Sherman later wrote in his Memoirs. "and could have walked into Resaca, and there have easily withstood the attack of all of Johnston's army with the knowledge that Thomas and Schofield were on his heels?.Such an opportunity does not occur twice in a single lifetime, but at the critical moment McPherson seems to have been a little cautious." (Sherman, p. 500)

For his part, Johnston appears to have prepared for just such a move as mentioned in his Memoirs: "We had examined the country very minutely; and learned its character thoroughly. We could calculate with sufficient accuracy, therefore, the time that would be required for the march of so great an army from Tunnel Hill to Resaca, through the long defile of Snake-Creek Gap, and by the single road beyond that pass. We knew also how many hours our comparatively small force, moving without baggage-trains and in three columns, on roads made good by us, would reach the same point from Dalton. Our course in remaining in Dalton until the night of the 12th was based on these calculations, and the additional consideration that the single road available to the Federal army was closed to Resaca by our intrenched camp." (Johnston, p. 316)

With such thinking supporting him, on the evening of May 9 Johnston dispatched the divisions of Major General William H.T. Walker and Major General Thomas C. Hindman along the railroad between Dalton and Resaca along with two brigades of Major General Patrick Cleburne's division. Johnston sent Major General John Bell Hood to take personal command of the situation at Resaca. In the meantime, the rest of the Army of Tennessee remained in the strong fortifications along the mountain range north and west of Dalton keeping Sherman's deceptive demonstration there with the Armies of the Cumberland and the Ohio in check.

On May 10, Hood ascertained that there was no longer an immediate threat to Resaca, reporting to Johnston accordingly. Johnston thus halted the movement of Walker and Hindman about halfway between Dalton and Resaca near the rail station of Tilton. He ordered Cleburne's two brigades back to Dalton. (Castel pp. 141, 144) Unclear as to what Sherman was exactly up to, Johnston kept his men ready to move toward Resaca at the first sign of trouble. On this day, Cantey's brigade was reinforced with Brigadier General Thomas M. Scott, the vanguard of Polk's two divisions from Mississippi. Note: Polk's second division, commanded by Major General Samuel G. French, was held at Rome, Georgia during the Battle of Resaca and did not participate in the battle.

On May 11, while McPherson was still entrenching at Snake Creek Gap, Johnston ordered Major General Benjamin Cheatham's division to camp along the road leading to Resaca in case he is needed. Johnston now had three divisions ready to move upon Resaca. At the same time, Polk arrived at Resaca with Major General William W. Loring, commander of his lead division accompanied by Brigadier General John Adams' brigade. (Castel p. 146, OR No. 687) Work to further strengthen the fortifications just west of the town intensified, including the clearing of a large area of trees around Camp Creek to increase visibility and deny cover to any attacking forces from that direction. By May 12, the rest of Loring's Division (Brigadier General Winfield Featherston's Brigade) arrived and the defensive preparations at Resaca solidified. In the meantime, McPherson's troops were resupplied and his army was now reinforced with Brigadier General Judson Kilpatrick's cavalry division and portions of the Army of the Cumberland that were gradually withdrawn by Sherman from the skirmishing action at Dalton. The Battle of Resaca was about to begin.